This morning I read an interesting series of three articles in La Presse. They ask whether Artificial Intelligence (admittedly a wide-ranging and vague concept) will be salutary or catastrophic.

One article puts the case for AI, one makes the case against, and the final one tries to balance the two.

The limited case for AI

Interestingly, the case for AI – whilst it is hyped by those who are interviewed – is remarkably flimsy. This does not mean that AI does not have its uses: only that its uses are narrow, and that it is narrowly focussed AI that shows most promise.

What do I mean by this? Below is the list, taken from the article, of the benefits AI will bestow (according to those interviewed) 1. I do not dispute any of these applications, but question their scope and their relevance in solving any major issue faced by society today.

So, here are the examples used in La Presse:

- to better anticipate and respond to migratory movements, providing governments and humanitarian agencies with information on where, and how, to deploy resources.

- to fight against climate change by improving climate models, better managing electricity infrastructure and networks, predicting demand for public transport, etc…

- to improve precision agriculture in order to manage water, nutrient, and pesticide use. In particular this would help less developed countries manage their resources better

- to devise new materials with specific properties needed for specific applications, by considering and modelling the vast array of possible fabrication processes and of permutations and combinations of basic elements.

- to sort potatoes so that restaurants get the size they want, consumers get standardized product, and reporcessors get the remainder.

- to analyze health data, and personalize health care (and medicine), based on analysis of patient and drug data.

- to improve medical diagnostics and to identify possible causes of illness.

- to understand rare genetic disorders, and to devise custom treatments

These are all interesting and worthy endeavours, but they are all of the same type: they are technical solutions to technical problems. AI cannot address any of the underlying social, economic or structural problems.

Why is the case for AI so limited?

The case for AI is essentially one made by STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) researchers. AI can be useful in finding technical solutions to intractable technical problems.

It cannot meaningfully address problems that stem (!) from politics, power relations, values or economics.

The problems AI can address are intractable simply because of the vast amount of information that one must marshal and process. AI is good at marshalling vast amounts of information (and will produce useful outputs, on the assumption that the information is of good quality).

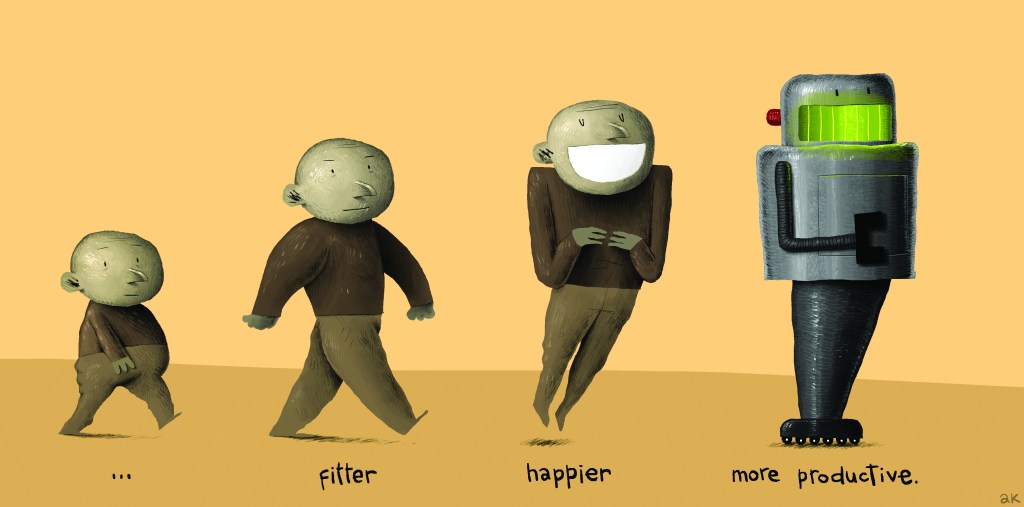

Source: https://cc.wopah.com/ Creative Commons licence CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 FR

The many questions AI cannot solve

Let’s go back to the list of problems AI can solve, according to the ‘pro-AI’ article in La Presse, and consider the underlying issues.

- to better anticipate and respond to migratory movements: AI cannot solve, or even begin to address, issues of poverty, colonialism, climate stress and exploitation that drive these migrations. The political, social and cultural complexities of these issues – as well as their ethical and moral dimensions – are not tractable by way of technical data crunching (however sophisticated).

- to fight against climate change by improving climate models: models do not fight climate change. The IPCC, and before it the Brundtland commission (1987) and the Club of Rome (1972) have, for the last 50 years at least, been warning of, and documenting, climate change and environmental degradation. This, too, is a cultural, political and social issue, overlaid with questions of ethics, morality and economics. At best, AI can help better manage the mess we’re in (whilst contributing to climate change, energy scarcity and water wastage – something even AI-optimists recognize as a problem with AI).

- improving precision agriculture in order to manage water, nutrient, and pesticide use. There is nothing inherently problematic about improving nutrient and pesticide use, though using AI to do so may be using a sledgehammer to crack a nut. Still, it is unclear what AI would add to traditional knowledge – it is only because traditional approaches to agriculture have been upended by financialization, globalization and climate-change, that this type of optimization becomes necessary. More fundamental research is also required to understand, and hopefully improve, the institutional and economic structures that govern agriculture and that are accelerating climate change.

- devising new materials. This is one of the areas where AI may indeed by useful: there are so many factors that interact when performing this type of research, so many possible combinations of elements and processes, that AI may indeed lead to useful discoveries. These discoveries, whilst complex, are also simple to test: once the material is prototyped, it is straightforward to establish whether AI has done a good job or not.

- sorting potatoes : this type of process improvement is great, but does not require huge datacentres and massive AI. The processes underying AI are useful for this type of problem, where the outcome can easily be assessed and does not require debate or political choices.

- health care and new drugs: there is little doubt that AI can assist in diagnostics and in improving drugs. It cannot, however, do much about inequalities in access to healthcare, the social and ethical issues involved in healthcare questions, nor about the economic imperatives that justify polluting our environment (and charging large amounts for new drugs), thereby creating new diseases that AI can then help attenuate (for the wealthy).

AI: a STEM solution to STEM problems

As in most articles that praise AI, praise comes from technologists who explore questions that are are amenable to technological fixes.

AI can do nothing to address underlying economic, social and cultural issues – yet these are often the issues that generate the very technical issues which AI is then called upon to solve.

AI also compounds these economic, social and cultural issues: its destabilization of the job market, its appetite for data (copyrighted or not), its capacity to surveil, its concentration of power in the hands of a few oligarchs, its energy and water use…. all of these problems, which AI exacerbates, will not be solved by AI.

Furthermore, as AI robs younger generations of their capacity to think for themselves, of their capacity to distinguish fact from AI hallucination, so society’s ability to understand – let alone solve – wider economic, social and cultural issues – will weaken.

Even though AI has no capacity to deal with open-ended social, cultural and political questions, which require informed debate and collective solutions, it will pretend that it does.

AI is quite capable of cobbling together ‘solutions’ to inequality and war from whatever it finds on the Internet… and an uninformed society will be quite capable of giving them credence.

***

1 This list resembles almost any other list that pro-AI apologists roll out. Although specific examples differ from list to list, the fact that AI”s useful applications are confined to technical STEM-like problems is a common feature; to which one may add summarisation of documents, provided one is not seeking too much subtlety. AI summaries are a sleight of hand: texts are approached as technical objects, not as cultural artifacts that carry meaning (which may be hidden, allusive, between the lines…). Once texts have been trasmuted from cultural into technical objects, then STEM solutions can be applied.