There can be no facts in a digital world

Over the last few weeks we have witnessed a group of spineless billionnaires bending over backwards at Donald Trump’s request, jumping when he says jump, altering information at his autocratic whim.

It isn’t just fake news by AI, bots and individuals that is enabled by social-media and the Internet.

Our current information systems also allows the rapid reconfiguration of entire information landscapes, including the instant rewriting of past (electronic) records. To the extent that much of our knowledge is now digital (e.g. many academic papers are digital only, and many books are too) then it is our knowledge base that can now be reconfigured at will.

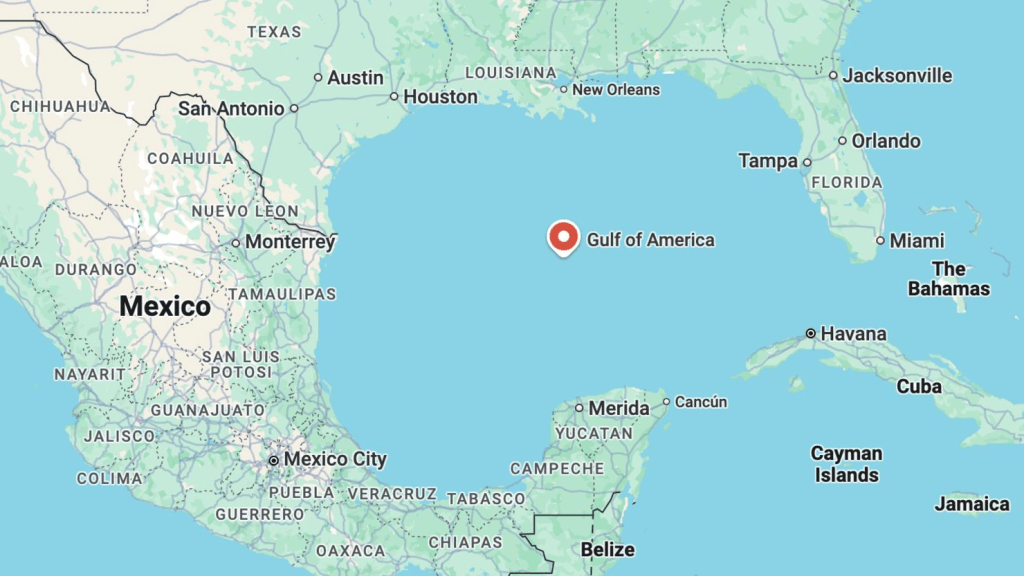

So, for example, Google, which has a stranglehold over much of society’s access to information, has renamed the Gulf of Mexico at Trump’s request.

Many organizations and ministries in the United States have taken down web pages which include references to gender, climate change, equity and other basic facts and processes.

Even more perniciously – this predates Trump – Amazon censors books on Kindle: as the New York Times points out, “recent automatic updates to e-book editions of works by Roald Dahl, R.L. Stine and Agatha Christie are a reminder of who really owns your digital media.”

In praise of paper and print

This flurry of change, the complete unreliabilty of what we read on-line (including this blog: has it been altered since it was published? will I, or someone else, make major edits?) highlights why books and print are the gold standard when it comes to verifiable and durable repositories of knowledge.

Naturally, some books are bad. Some books are factually incorrect. It is also possible to gather, burn and shred books.

But, if you hold a book or printed magazine in your hands, you can be sure that its content today is the same as it was yesterday.

You can also be sure that a specific edition of the book or magazine is identical across its multiple prints: this means that books and magazines create shared knowledge, which can be discussed.

So, if I pick up my 2004 edition of Jonanthan Rauch’s ‘Gay Marriage’ (published by Owl books, 1st edition, paperback), and turn to page 180, I find the sentence: “As so often seems to be the case, the gay left and the antigay right, nominally bitter adversaries, have a way of working together against the centre. They may agree on little else, but, where marriage is concerned, they both want the federal government to take over“.

This text, which I first read 20 years ago, is strictly identical today. Anyone with the same book will find exactly the same text at the same place.

Neither Musk, Bezos, Google, Trump, Zuckerberg, AI or keepers of webpages can alter this text; and none of them can, despite their information technology, emulate these qualities of paper and print.

A final thought about AI

Incidentally, this tells us something about AI: general AI obtains its information from electronic sources. We are witnessing how completely unreliable these sources are, how they are curated in real time by tech-platforms at the whim of their craven bosses.

Would you trust AI?