In a previous blog I argued that Montreal (and, by extension, other non-European cities) should cease to look with envy at European active transport and urban planning solutions. I made similar points a few years ago when I also expressed exasperation at Montreal looking to Copenhagen for ‘solutions’.

There have been a few comments on my post, some in agreement, some raising questions, two of which I try to address below. Why should Montreal think for itself? What am I proposing?

Why should Montreal think for itself?

Some of the reasons are spelled out in my previous blogs. They boil down to the fact that Montreal has different urban morphology, public transport, and weather. I think that these differences are well -understood by most commentators.

The question raised therefore focuses on whether we should entirely ignore the European experience, or whether we can learn from it.

In a limited way we can certainly learn. We can learn from the political commitment to invest in alternative mobility; we can learn from specific design solutions to specific small scale problems (such as how to integrate bikes into a traffic roundabout; how to design lanes that allow cars, pedestrian and bikes to co-habit; how to retro-fit a busy commercial street into a pedestrianized area,.. and so).

Why do I say these are limited lessons? They are limited because these small-scale design solutions do not address big questions such as weather, topography or urban morphology.

Urban Morphology

I use the term ‘urban morphology’ in a generic way, to refer to the layout and structure of the city at a variety of scales: here I will just focus on the regional scale.

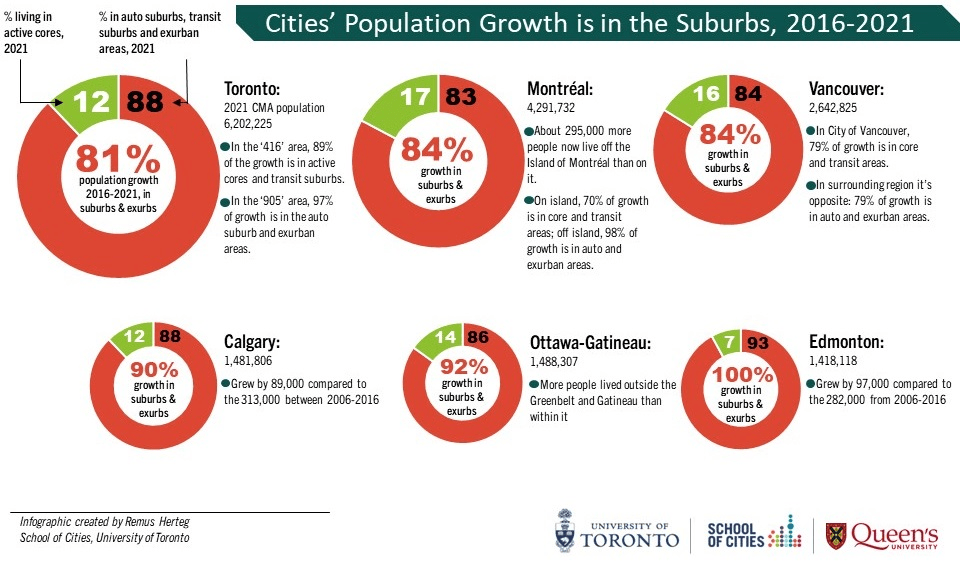

Between 2016 and 2021, 84% of Greater Montreal’s population growth was in suburbs and exurbs, places where a car is necessary to get around (this is how David Gordon and his team have defined suburbs and exurbs). Furthermore, only about 17% of the city’s total population lives in the walkable core, with a further 13% living in suburbs that have some transit use (typically low – but non-zero – and principally for regular commutes).

So, 83-84% seems to be a key number: around 83% of Montreal’s populations lives in suburbs or exurbs (a few with some public transport), and 84% of the agglomeration’s growth is in these suburbs. Only 17% of the population can conceivably use public or active transport for day-to-day activities.

Why insist upon this? Because if we, in Montreal, are serious about decongestion and environmental issues, we need to find solutions to the correct problem.

The problem is NOT how to get more bike lanes in the urban core. I am all for them, but I do not fool myself into thinking they will have a major environmental impact; and they will only serve to decongest if there are viable public-transport alternatives (but see my previous blog).

The problem is how to allow the remaining 83% of Montrealers – i.e. 3.4 million people – to get around, and out of, the city in alternative ways.

This does not merely mean getting people to downtown and back at rush hour. In fact, fewer and fewer daily trips are to and from downtown. Many more trips are across suburbs, are to go to school, to the leisure centre, to shops. How can this be organised in such a way that cars are used less (given Montreal’s urban morphology, I simply do not see how we can get rid of private vehicles in the foreseeable future)?

And, even for those people living in the walkable core, cars are often necessary: there is virtually no inter-urban public transport in Canada, and there is virtually no way to get out of town for leisure activities (like cycling, swimming in a lake, camping…). So many people who live in walkable neighbourhoods, and don’t use their car day-to-day, still need a car in order to get out of town, visit-relatives, go to meetings, etc… Car-share, a partial and often clunky solution, become onerous as soon as the car is needed for a few days (e.g. camping trip, visit to family in a rural area…).

My point is that Montreal mobility, environmental and planning thinkers need to fully integrate this reality, and devise approaches that acknowledge this.

Public transport

Active transport requires good enough weather (see below), and, if the weather is bad, if the distance is too long, or if a person is living with a disability, it requires excellent public transport – that truly caters for all people – able or not, carrying bags or not, herding children or not.

Montreal has public transport that is fairly decent when compared to many North-American cities: but, when compared to Europe it is modest. Furthermore, public transport is only viable within about a 10km radius of downtown (where there is a dense bus and metro network). Beyond that it is infrequent and sparse at best, and it is simply impossible to get out of town: there is no trains or buses to rural or resort areas, and very few, even, between major cities in the province.

We simply do not have the public transport infrastructure – local, regional and inter-regional – that many European cities have. I am not pointing fingers nor trying to lay blame: North America developed in a different way than Europe did.

My point is that Montreal mobility, environmental and planning thinkers need to fully integrate this reality, and devise approaches that acknowledge this.

Weather

Cycling in Copenhagen (or Paris, or even Stockholm) is not the same as cycling in Montreal, each having its own climate and challenges).

In Montreal, – whatever the design, investment and traffic-reduction solutions – we are faced with a winter that lasts at least five months (mid-November to mid-April, with snow possible from late October to early May).

Our winter typically has wild swings in temperature: a few days ago it was +10C, then it snowed, and snowed again, then it was -15C (yesterday morning as I commuted to work), then it was -9C (and snowing again) today. Exceptionally, there are no temperatures above -6C forecast for the next two weeks, which is GOOD news.

More often than not there will be a day, or even a few hours, every two or three weeks when the temperature rises above 0C, melting snow that has been stacked to the side of roads and cycle tracks, often creating thick sheets of ice that are difficult to remove from bike lanes (bikes are not heavy enough to melt ice as they roll over it, so, unlike on roadways, the ice does not get worn away). This is particularly snow in early and late winter, but climate change is making this quite common in the middle of winter too.

Why these technical details? Because it is these details (to which I should add the simple fact of commutes that, in early morning or evening, are usually performed in temperatures below -10C, and, often enough, below -20C) that Montreal cycling advocates and designers also need to think-through.

How can we avoid ice build-up after thaws?

How can we ensure proper cold-weather drainage?

How can we ensure that brakes and locks don’t seize up?

How can we ensure that there are adequate – and WARM – places for cyclists to peel off their clothes and hang them to dry? (which, paradoxically, are often very sweaty in winter since, to keep warm, one blocks off air-flow: I am often both cold and sweaty after a winter commute).

Finally – in this non-exhaustive list – do we seriously think that cycling is a viable winter solution for getting around?

Yes, it is POSSIBLE to cycle all year. I do so, as do quite a few other people; but many eminently sensible people think it cold, dangerous, and difficult to reconcile with a public-facing job. Many other eminently sensible people – even those with cargo bikes – find that hauling children and goods around on snowy and icy surfaces, often in bitter winds, is simply no fun.

My point is that Montreal mobility, environmental and planning thinkers need to fully integrate this reality, and devise approaches that acknowledge this

What am I proposing?

This question comes from action-oriented people. If a problem is raised, then a solution should be proposed.

However, rushed solutions, especially if we understand the problem poorly, will not be good solutions.

I make no claims to ‘have’ a solution: any urban planning solution(s), that involves culture, habits, livelihoods, investment etc… needs to be discussed first.

But those discussions need to rest upon a good understanding of the problem. If we accept that the overarching problem lies at the intersection of environment, mobility and congestion, then the questions to think about, before searching for solutions, are:

- how does this overarching problem play out specifically in Montreal, given Montreal’s specificities (some of which I have outlined above, emphasising differences with European cities that are often used as exemplars)?

- can we suggest, in broad terms and in principle, some ways of addressing mobility in the suburbs, and mobility in the absence on inter-regional and regional transport?

Once there has been some serious and collective thought given to these two high-level questions then, and only then, will it be reasonable to critically assess the extent to which some European ‘solutions’ shed light upon Montreal’s problems.