In Montreal there have been repeated calls by a prominent environmental organisation – Conseil régional de l’environnement de Montréal (CRE) – to price on-road carparking. The latest reminder of this was a few days ago in La Presse.

I share many of CRE’s motivations, and would like to see less car dependency. However, I believe that campaigning for the systematic pricing of on-road parking, including in residential areas, is a strategic mistake.

In a nutshell, increasing the cost of car-ownership before alternatives are in place is a regressive approach, hurting poorer car-owners whilst leaving wealthier ones unscathed. A possible consequence is backlash against attempts to orient people away from car-usage.

Much as I would like to ignore this possible unintended consequence, current Canadian backlash against the carbon tax lends credibility to my concern.

I set out my reasoning in more detail below, and then tentatively propose a few alternative approaches that could (?) bear more fruit.

In North American cities, cars are a necessity, not a luxury

There seem to be two types of people who can live without a car in North American cities.

First, there are people who live close to downtown and who are able to cycle, use public transport, and rent cars when necessary (about 5 to 10% of the population of metro areas in Canada). This is a lifestyle choice, only available to a few, given the limited geographic extent of reliable and frequent public transport and of car-sharing.

Second, there are poorer people, typically relegated to suburbs and/or places of lower accessibility, and who cannot afford cars. For many of these people, being able to afford a car would save time, would allow access to more and better jobs, and would be a good thing given the current configuration of North American cities and the location of jobs and services.

[…before you object that people work from home today, remember that it is predominantly well-educated office workers who do so, not factory workers, nurses, warehouse workers, utilities workers, teachers, store attendants, cooks, street cleaners…]

Thus, except for maybe 5 to 10% of the population for whom mobility alternatives are feasible, most people, wealthy or poor, need access to a vehicle. This is not necessary to survive, but is necessary to participate fully in current urban society in Canada.

If mobility (i.e. access to jobs, access to rural areas, access to grocery stores, access to daycares…) is considered a basic capability for North American citizens, then having a car is – for most people – a way to realise this capabilty (I am here using vocabulary and concepts from Amartya Sen’s and Martha Nussbaum’s capabilities-based theory of justice).

Car sharing systems are a very partial solution, and difficult to implement outside of central high-density neighbouhoods.

Increasing car ownership costs will decrease mobility for poorer people

The problem with systematically pricing on-road parking is that it is a regressive system.

Although the cost of on-road parking would be the same for all – say $1000 a year1, or it may even be slightly progressive, costing more for larger cars – it will hit poorer people hardest for two reasons:

- they have less money, so a fixed (or faintly increasing with car-size) price will represent a far larger portion of their disposable income than for wealthier people2;

- they cannot avoid this new cost, whereas wealthier people often have private drives or underground parking places: they do not rely on on-road parking.

This would not be a problem if there were genuine, practical, mobility alternatives that, for example, allow children to be transported, suburbs to be reached, jobs to be accessed, groceries to be delivered, leisure activities to be undertaken – all within a tight timetable.

Currently, practical alternative mobility does not exist, except for a small minority of (often young and/or childless) people living in and around some downtowns. Even they may find it challenging to go camping, take a rural hike, or take a dip in a lake without a vehicle – though it is for these people that car-sharing works best!

Phasing the transition away from cars is crucial

Like the CRE, I have read the interesting HEC report that computes the private and social costs of various modes of transport.

The HEC report argues that the high private and social costs of car ownership should spur public investment in alternative modes of transport : it does not suggest that adding to the cost of car-ownership would be desirable.

Yet the CRE uses the HEC costings of car-ownership to suggest that increasing these costs would be socially beneficial : in so doing, the CRE overlooks the high cost, outside of some specific urban centres, of not having easy and immediate access to a car.

The CRE, HEC and I agree that there are solid reasons to move away from car culture towards softer modes of transport: the real problem relates to how this can be achieved in an equitable way.

The risk of backlash: using a car is not (currently) a choice

We are seeing the backlash problem in Canada with respect to the carbon-tax. Almost all economists and environmental groups think such a tax is a good idea (as do I): by increasing the cost of carbon emissions it forces companies and individuals to think more carefully about their choices. Furthermore, this tax has been designed to be revenue neutral (so taxpayers, over a tax cycle, do not in fact lose any disposable income, thanks to rebates).

Yet even the NDP is backing away from the carbon tax because of the way it is perceived.

Many Canadians feel they have no choice but to use their cars : given our settlement patterns, they are correct. Thus, they perceive the carbon tax not as a way of channeling choices (because they have no choice) but as a way of making them pay for abstract and long-term wishes formulated by environmentalists.

Populist politicians, such as Poilievre, are leveraging this into political support: I am concerned that, without realistic mobility alternatives for many people, the carbon tax (and other attempts to increase the cost of car-ownership, such as suddenly hiking parking costs) actually lead to a regression of environmental policy in Canada.

Unfortunately the path to reactionary (and environmentally regressive) election results is paved with good intentions. I am concerned that by touting an appealing but (fiscally) regressive agenda, the CRE may inadvertently set back the important cause of trying to reduce car usage.

So what possible ways forward are there?

After critiquing the CRE approach (whilst being sympathetic with its objectives), it behooves me to make a few (albeit tentative) suggestions.

These three suggestions are premised upon the fact that, given the current configuration of cities, services, leisure, job opportunities and population, vehicle ownership is essential (for most people) as a basic necessity of everyday life.

- acknowledge and discuss the problems of increasing the cost of car ownership – especially with less wealthy car-owners – and work with them to understand what would entice them away from driving. It is not helpful to present the rising cost of car ownership as an unequivocal benefit.

- alternative modes of transport need to exist, and be widely deployed, before costing people out of car ownership. Otherwise, increasing the cost of car ownership will create hardship, felt most accutely by less wealthy people living away from the hyper-core of urban centres (remember, 90 to 95% of urban Canadians live away from the hyper-core of urban centres).

- consider restrictions to traffic flow3, rather than increases in ownership cost, as a way to limit car use. Congestion – a consequence of restricting traffic flow – affects all car-owners equally, and does not hit poorer (or wealthier) people harder. In this way, it will be all citizens who clamour for, and then use, alternative transport solutions, not just poorer people who cannot afford cars (and who will typically be ignored by politicians).

***

1 CRE estimates the current cost (to the city) of on-road parking at $1275 per annum, a cost which, it argues, should be passed on to car owners.

2 Car ownership is expensive, but not prohibitively expensive for many households: I recently purchased a low mileage 2015 vehicle for $8000. Slightly older ones are available for $5 or $6000, and clunkers can be obtained for a few thousand less. Yes, there are maintenance costs, which, on a vehicle such as the one I bought, will hopefully turn at about $2000 a year for a few years… I am mentioning this to counter the argument that car-ownership is only accessible to wealthy people. It is not necessary to purchase a $40 or $50 000 car to be motorised. Car-ownership is indeed a major expense, but is accessible – at considerable effort – to many households on modest incomes: my argument is that this effort should not be further added to, because, for now, cars are a necessity, not an option, for most owners.

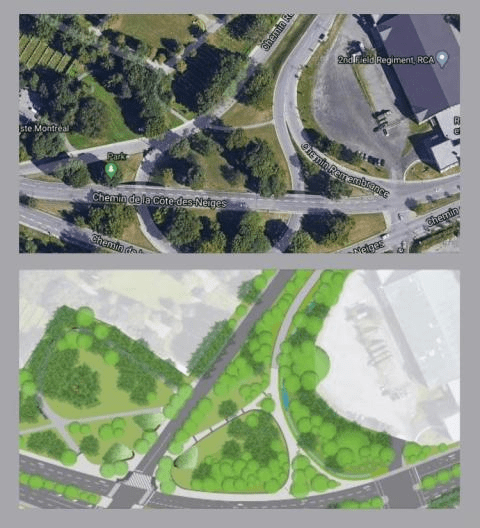

3 Yesterday was Montreal’s cycling Grand Prix. Three of Côte-des-Neiges’ six lanes were closed, yet traffic was getting through, more slowly, on the two lanes set up on the side that remained open. Why not make this arrangement permanent, extending the great work that has been done on Chemin Rememberance, which has been reduced from a four lane road to a two lane road, thereby opening up a superb bike and epdestrian parway into Mount Royal park?